IPA: The theory and beyond. Is knowing the IPA essential? Do you use phonemic script in class? Why or why not? #ELTchat Summary 22/02/2012

Full title of #ELTchat on February 22nd 12.P.M. GMT

This summary was contributed by Rachel Appleby, alias @rapple18

Introduction

Dealing with pronunciation in the classroom is one of those things that comes naturally to some, is consciously avoided by others, and is a bit of a bête noir for a few. We know these symbols are also something that many students fight shy of, especially at lower levels, and in particular if they are coming to English from a different script (Cyrillic, Arabic, etc.). So it needs handling with kid gloves. Or does it?

The ELT chat on this involved some 15-20+ participants from all leanings, promoting plenty of meaty discussion. Some still remained unconvinced by its value at the end of the hour; others left excited to give it another go. Issues touched on, and still worthy of future discussion could include …

– Sounds vs spelling with IPA

– Different Englishes / accents: exploiting IPA

– Teaching dyslexic students: how can IPA help?

The issues covered, in a nutshell, included

- Do we, teachers, know all the symbols?

- How important is it for us to know and use them?

- How important is it for students to recognize and use them?

- Where do we stand with different Englishes, and a chart that focuses on RP?

- Concerns and reservations

- Is the use of the IPA on the decline?

- Activities: examples of how we use the symbols in the classroom

- IPA and dictionaries

- Apps

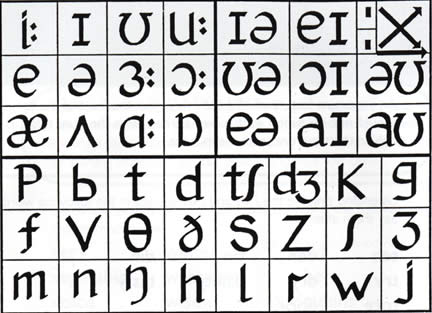

Image from Peter Ladefoged’s home page

For those needing a bit of background and unpacking, the IPA, or International Phonetic Alphabet comes up on Wikipedia as follows:

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is an alphabetic system of phonetic notation based primarily on the Latin alphabet. It was devised by the International Phonetic Association as a standardized representation of the sounds of spoken language. The IPA is used by foreign language students and teachers [and many more…]

IPA symbols are composed of one or more elements of two basic types, letters and diacritics. For example, the sound of the English letter ⟨t⟩ may be transcribed in IPA with a single letter, [t], or with a letter plus diacritics, [t̺ʰ], depending on how precise one wishes to be. Often, slashes are used to signal broad or phonemic transcription; thus, /t/ is less specific than, and could refer to, either [t̺ʰ] or [t] depending on the context and language.

Extract from Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Phonetic_Alphabet

For the purposes of this online chat, it seemed that participants were mostly concerned, and by and large familiar, with the version arranged by Adrian Underhill, the phonemic chart, which is exemplified here (in an edited version). It’s also on the walls of many IH classrooms:

http://www.englishclub.com/pronunciation/phonemic-chart.htm

Underhill, A. (1994). Sound Foundations. Heinemann

Adrian Underhill’s Phonetic Chart

Terminology, as such, didn’t come up (phew!), but in case you like to collect these, here are a few key words:

phonology /fəˈnɒlədʒi/ the speech sounds of a particular language; the study of these sounds

phonetics /fəˈnetɪks/ the study of speech sounds and how they are produced

phoneme /ˈfəʊniːm/ any one of the set of smallest units of speech in a language that distinguish one word from another. In English, the /s/ in sip and the /z/ in zip represent two different phonemes.

A big thanks to our efficient moderators, Shaun Wilden and Berni Wall, who got the ball rolling, kept us on track despite interruptions – both real and virtual – and ‘wound us up’ – in the best sense – at the end.

Starter questions:

How’s your knowledge? Is it essential to know and use?

Cards on the table, it seemed that most of us had a reasonable to good familiarity with the key sounds on the chart, although there are still some sounds many of us have to check.

In terms of using the chart, some participants claimed “I can’t imagine teaching (or learning) without it” and “I use the chart everyday with sts at all levels when needed”. Others noted, “I think is it a very useful shorthand to explain things that otherwise take longer but only where it’s familiar”, while another mentioned, “Never felt the need to use it myself”. Some only use the symbols if there is plenty of time, and if the course is pronunciation-intensive. It was generally agreed that there are some sounds which it’s very important (even essential) for teachers to know.

There was also discussion on mono- and multi-lingual classes, although not much agreement. Certainly in monolingual classes it is easier, or it helps, to work on sounds which are specifically difficult for that L1, but there are obviously also teachers in multilingual contexts who find the symbols useful.

It sees many of us have fun ways to incorporate the symbols into lessons, but there was an overriding feeling that they need to be integrated as far as possible, and not dealt with as a one-off, just on occasion. There are certainly classes where both teachers and students enjoy working with the symbols (for ideas and activities, see below), although skeptics too: “I can understand why you’d find it useful, but I think it’s a personal choice. Never felt the need to use it myself.” And “I understand why I don’t use them” – explaining that it was a question of time and priorities.

The issue of sounds and spelling came up – and is perhaps one worth digging more deeply into another time. “I teach a pronunciation class. IPA raises awareness of sound as distinct from spelling.”

A couple of people mentioned their students use the symbols, probably in hand-in work, but also suggested that the extent to which those students understood the symbols was dubious! A long vocab list with words on phonetic script is impressive, but not necessarily the least bit helpful if the students doesn’t know what the symbols are, or mean. Now that it’s easy to copy-paste them from online dictionaries, the homework ‘gets done’, but without effect!

Finally, it was mentioned that use of the phonemic chart, or the symbols at least, can raise awareness of those sounds not in the students’ own L1; additionally, although students may not be able to produce, to native speaker level, various sounds, an understanding of the sounds and the differences does help them with listening skills.

A few words of caution: some students feel the symbols are ‘a new language’, which can simply add to the overload of information. Learning two scripts (e.g. Ukrainian students learning English) would be particularly vulnerable to this syndrome. Additionally, although many benefits were mentioned of students knowing (some of) the symbols, students of English in the Far East, who tend to demonstrate more anxiety over listening texts, were even more fearful when it came to the addition of symbols, which contrary perhaps to the teacher’s hopes, simply exacerbated the situation. And finally, whether the symbols actually give students more confidence. This remained unanswered.

Overall, many felt that yes, we should know and use the symbols, but that it does depend on the contexts and situations we are teaching in.

Different Englishes

A major issue in using these symbols is the variety of Englishes we speak – not least ‘Merican English. I personally felt that there were more questions than answers (hence a suggestion for another ELTchat topic another day(?), but some had some answers:

- Course books use these symbols to reflect standard pronunciation, but these can also be used to show differences.

- Some chatters had used the symbols for highlighting specifics in e.g. a Glaswegian or Yorkshire accent.

It was stressed, however, that it’s important to address the variation in accent. Several participants agreed that the IPA symbols are representations of sounds, and that speakers of different Englishes also project their sound onto the symbol.

Demise of IPA

Another issue that arose was whether IPA was being less used. A number of reasons were given:

- Perhaps because pronunciation work as such is dealt with less in the classroom nowadays.

- Do teachers or students really feel such pron work (with symbols) is useful or credible? Do the students expect to be working with pron symbols?

- Focus on language production has moved from accuracy-based to intelligibility. On this, if sounds wrongly produced result in a breakdown in communication, then obviously work on symbols might help. I would argue whether “I took my cat to the wet” would actually be misunderstood or misinterpreted, but the point was understandable.

- Due to the availability of fancy electronic dictionaries which just ‘say’ the word; thus the students can simply listen and repeat, and don’t need to read or understand the symbols.

It was mentioned that school reports (‘visits’) tend to note that not enough pronunciation work is done. (It’s easy to ‘X’ a box on a form.) Perhaps IPA seen as a top-down supervisory thing?

Overall, I felt there was little agreement, but it made for a fruitful discussion.

Dictionaries and Self study

Here there was considerably more agreement, in that familiarity with IPA helps students be far more independent. They can use dictionaries more effectively, and are thus able to study outside the classroom. (As distance and blended learning become more ‘the norm’, this has to be an important point.) Some participants, although perhaps reluctant to do too much IPA work in class, were keen to point their students in the right direction for self study resources if they were interested.

Activities / purpose

A wide variety of activities were offered. I think that everyone agreed (or would agree), that an overriding consideration is that phonemics are incorporated into teaching, and that they’re not dealt with on their own, i.e. that these symbols are simply part of the whole process. Furthermore I would add (in case I missed it!) that it’s important that the symbols are presented / used / practised in meaningful ways, i.e. in context or in words which students relate to easily.

Some of the ideas

- Scrabble with sounds in place of letters: helps awareness of phonemes, and is fun.

- Go through a text and identify every use of ‘X’ sound

- The teacher writes 2 similar sounds on the board. S/he plans what order to say them in. The teacher speaks very quickly, alternating between the sounds. The students write them down. (I guess this could be done with words / minimal pairs.)

- Writing sound titles in IPA and getting students to decode. Students can also then write song titles. (The same could be done, e.g. with film titles.)

- Transcribing words / phrases / sentences written in IPA

- Warmer / Filler / Vocab revision: pairing students up: each has a word written in IPA. “Find your partner”, e.g. collocations / synonyms / opposites etc.

- Warmer / Filler / Vocab revision: categorizing words according to sounds

- Students write secret messages to each other in IPA

- IPA flashcards: listening games – minimal pairs – students hold up the sound card they hear

- Students compile their own words lists – including pron in IPA

- Showing students how connected speech blurs words together e.g. Green Park /grɪːmpaːk/

- Transcribe a conversation (e.g. someone did this from BBC Radio 4) into phonemic script. S/he told them it was a puzzle. They worked it out.

- Write a letter to your students in phonemic script (good at start of a higher level course, or on CELTA TT courses). Students reply to you, and write 1-2 sentences about themselves.

- Raise awareness of problem sounds. Useful to highlight these in words and connected speech

- Using IPA to raise awareness of sound as distinct from spelling.

- Using IPA to focus on difficult consonants (v/w) / vowels and diphthongs

- Vowel length can be shown with IPA to avoid what this would otherwise be: “I go to the beach at the weekend”

- Introduce a limited number (e.g. 6) vowel sound symbols. Students listen to a text, and find just those sounds. (I guess this would be a follow-up activity after content / comprehension focus.)

- Building up a repertoire of key sounds / symbols for one group; obviously it’s easier if it’s a monolingual group as they’re going to have the same problems, but certain sounds do come up again and again.

Pronunciation apps

Although there were pro- and non-app users online for the chat, it was clear that if we were going to use and/or recommend these to students, we’d need to introduce them well and teach them how to use them, but that they can be a very empowering tool.

Here’s “Sounds”, the (free) Macmillan pronunciation app. http://www.soundspronapp.com/

There also seems to be a second version for £3.99 which offers a bit more:

http://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/sounds-the-pronunciation-app/id442713833?mt=8

I downloaded the free one. It has 3 basic functions:

1. Read IPA / write the word: demo’d with earth / mirror / iron

2. Read the word / write in IPA: demo’d taxi / house / nothing

3. Hear the word / write in IPA: mirror /

4. There’s also a guide to using the phonemic chart: a video with Adrian Underhill.

British Council app. http://learnenglish.britishcouncil.org/en/mobile-learning/sounds-right “Teachers and learners of English have now got a new tool to help master the sounds of the English language thanks to the British Council’s latest iPad pronunciation app. Sounds Right is an interactive Learn English pronunciation chart with sounds grouped by vowels, consonants and diphthongs complete with examples of each in use. It is available to download from the iTunes store for free.”

Participants felt that, yes, apps are probably useful for students outside the classroom, but beyond that, didn’t feel they had a place in the classroom. It clearly depends, too, on the students’ interests. Another added, that they’re fine “if it’s your thing”. The Macmillan app was praised as being both “a thing of beauty” and “very well made”.

Someone mentioned interactive IPA charts (see below, BC site). They exist, but there was minimal discussion, and perhaps it was presumed that in fact they are rarely used.

Useful links

http://ipa.typeit.org/ writing on the computer in phonemic script: “This page allows you to easily type phonetic transcriptions of English words in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). You can edit your text in the box and then copy it to your document, e-mail message, etc.”

Other BC phonology websites:

http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/activities/phonemic-symbols

“Help your own and your students’ pronunciation with our pronunciation downloads. There are 44 A4 size classroom posters of phonemic symbols with examples to download. The posters are in Portable Document Format (pdf) and have been attached in a zipped folder.”

And this: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/activities/phonemic-chart

“This is the new British Council phonemic chart. Help your students hear the sounds of English by clicking on the symbols below. Click on the top right hand corner of each symbol to hear sample words including the sounds.” It also includes activities.

Some final comments

As a summary, some final comments included the following:

I’m “not an IPA fan but this discussion has got me curious! Going to take a chart to my class tonight”

“25yrs teaching and I feel like I’ve got a new toy to play with!!!”

“Teaching IPA is definitely a time investment but saves lots of time later on”

“Like everything else, depends on how you use it, and if it’s effective for your students. If it is, then why not?”

“Important for sts to be aware of it = my first goal in class, and then go from there”

“Introduce it bit by bit – and keep it fun”

And, sadly, “I remain unconvinced – who wants to try to convince me?”

Please add your comments and your experiences on using IPA symbols with your students – especially if you’re newly inspired. Perhaps we can, still, convince the unconvinced!

Here’s to the next stimulating ELTchat – not to be missed! Thanks for the privilege! Rachel

About the author

Rachel Appleby teaches English at ELTE University in Budapest (language, culture, communication skills, business, and methodology, on both the BA and MA programmes).

She also teach B.E. freelance and is a teacher trainer (CELTA, LCCI). She’s co-written a number of course books and teachers’ books for OUP (inc. the Business one:one series), and The Business Advanced (Macmillan). She is currently working on two levels of the new edition of International Express (OUP). She is an occasional contributor to the reviews section of the ELTJ. She is learning that twitter and ELTchat can be a life-changing and time-consuming experience!

She is @rapple18 on twitter

12 Responses

For the half of the world’s population whose first language does not use a Latin script, IPA is a waste of time.

In my situation, I teach students in Taiwan 40 minutes per week. Their first language uses traditional Chinese script and its more than 10,000 characters take many years for them to master. As one of the speakers mentioned, IPA is just another level of complexity to impose on them, which is why we don’t do it.

Students are quite capable of learning to speak reasonable English without IPA. For example, the excellent Synthetic Phonics approach used widely in the U.K. (and increasingly in the USA) offers a more straightforward system linked closely to English spelling.

Once students know some reference sounds used within key words, they can use them to learn new words, rather than trying to recall isolated, decontextualised symbols.

Although I had to endure some IPA as part of my own formal training, I see it more as a tool for professional linguists than for second language learners.

I quite understand – don’t complicate their lives! You’ll have read that there were others involved in the chat who weren’t happy / whose students were not keen on using the IPA for similar reasons. What you say about knowing “some reference sounds used within key words” makes a lot of sense. However, I would never use these symbols in isolation: they really need to be integrated and dealt with within a meaningful context. Some teachers and students find them very helpful.

Only use the tool if it helps!

Thanks for sharing your thougths!

[…] For a much longer list of activity ideas see the previous #eltchat on a similar subject […]

Thanks for this article Rachel! I found the IPA chart really helpful during my TESOL training because the students in the training classes were already familiar with it. I’ve just started teaching esl to Arabic speakers and I’m thinking of introducing IPA to them. Arabic is a very phonetic language in that what is written is pronounced and so English pronunciation (especially silent letters and letters that have more than one sound) can be confusing. I’m hoping to experiment with it in the next few weeks and will let your know how I get on!

Saba

sabaandthecity.blogspot.com

The IPA is not English friendly so it’s not used for teaching reading in USA. What can be used is truespel phonetics, which is the only English base pronunciation guide spelling system. It can be learned in 15 minutes by high school ESL students who judged it better than the IPA for learning US English. http://justpaste.it/course2

I was an English language teacher for 10 years in Brazil. When I was at the university, taking the language course, IPA did not make much sense at first. However, after taking a book from the local library and attentionly reading its content, I became so addicted to IPA that I included part of the time to teach my students to interprete those “strange” symbols present in their grammars, dictionaries and course books. The result is that my students all agreed that the English language should be transformed into IPA. All of them had better pronunciation compared to those students whose teachers did not emphasise IPA in their classes. I started to learn Arabic and I’m am using IPA to help me learn words. In order to test my own skills, I very often compare the Arabic words with IPA pronunciation and pronounce them before listening to a CD. My pronunciation is extremely close to the tape thanks to IPA system. I don’t know how Arabic people learn English and I don’t know what their techniques are to help them learn English sounds, but I assure you that IPA has been very helpful.

Great case for using the IPA – many teachers go against it simply because they are not familiar with it

Thanks for commenting

Surely if they can learn and memorise 10,000 characters then it wouldn’t be too much of a challenge to add in 44 more for English, especially given that the majority of the consonants are the same as the Roman letters of the alphabet which they will surely have to become familiar with if they want to read or write anything in English.

Is the fact that students are quite capable of learning reasonable English without using IPA a satisfactory reason for ignoring a tool which could improve their English pronunciation further?

Working in India, the director of the school said that IPA was useless, that the students would rebel if you tried to use it, etc, but it simply wasn’t the case. Used well, the students reacted really positively and for a country like India this was an excellent told to move what was often very good but hard to understand English towards something that was far more mutually intelligible.

I suspect the main reason your students’ pronunciation improved was because you had them practise it, not because you used IPA.

As for writing English with IPA; written (typed) English has evolved to be efficient. IPA is not efficient to write or type (even if you changed keyboards).

Further, the variety of Englishes is preserved by the diversity in spelling. If one alphabet was used, then there would be a greater possibility of one group succeeding in defining what is ‘proper’ English. I just don’t see the need to simplify a language at it’s expense.

Eventually I do see an international language evolving from English (with lots of influence from other languages), that is a simplified version of English.

I’m all in favour of IPA for linguists wishing to record, understand and preserve languages. I do not think it is good for teaching the masses.

Try writing “forms of English” or “types of English” if you want to get some respect as an educator or English teacher. In the English language, the word English and the words for other languages are non-countable.

Dear Mark

Are you 100% sure of what you have just posted and did you in fact bother to check the accuracy of your comment?

Here are the results of a google search for your perusal

Linguists and respected educators and scholars know that you are wrong – the term “world Englishes’ is included in many standard linguistics and sociolinguistics textbooks, but did you know this, respected educator?

I am guessing you did not.

Also, apart from not knowing your stuff, what you wrote about the blogger, a highly respected educator, materials writer and speaker, doesn’t commend you.

Oh well, it takes all sorts of people to make the world, ignorant blog trolls included.

I see you did not mean the blogger but one of the comment writers – you did not even read the post but just came here to troll! Shame!

Comments are closed.